LIBERACE: Interview with playwright Brent Hazelton

By Henrik Eger

Eger: What was the impetus for your writing the script?

Writer Brent Hazelton

Hazelton: A deadline! The project was an emergency replacement for a very last-minute and therefore unexpected void in the 2010/11 season at Milwaukee Repertory Theater, where I serve as Associate Artistic Director and Director of New Play Development. Our Artistic Director, Mark Clements, gave me the assignment, even though—aside from toying around with some literary adaptations which no one has or ever will see purely for mental exercise—I had never written a play before. Regarding the subject, it would frankly be a lie to say that I had long-harbored a burning desire to tell Liberace’s story—or even considered it before the project was assigned to me. Having grown up in Wisconsin myself, I knew that he was “one of ours” (he and my father grew up in the same first-ring Milwaukee suburb, forty years apart), I had the vague recollection from my ten-year-old self that he had died of AIDS and that at the time that was in some way a very big deal, and I had an even earlier strikingly vivid memory of him performing on the Muppet Show. Beyond that, I knew absolutely nothing about him—aside from the general image of opulence and excess with which he worked so hard to associate himself, and a general sense that people seemed to enjoy satirizing him a great deal.

Eger: Describe the process of researching the material.

Hazelton: In addition to my theater background, I’m also a history major by education, so the compulsion to exhaustively research and dig deep for every potentially useful detail is second nature. Particularly so when facing the prospect of a blank computer screen, a serious dearth of knowledge, and an opening night already on the calendar and tickets already on sale, given that we’d announced the season in which LIBERACE! would play two months before I even got the assignment to begin writing it!

My first step was to collect as much source material as I could. And, thankfully, there’s no shortage! Liberace worked very hard to message his own persona and create a certain mythology around himself, and in addition to a consistency of performance and many of the same rote answers in interview after interview, he published several books, including an autobiography that reads a bit more like a book-length press release and a few coffee table picture books (which are fascinating and instructive more for what they don’t say than what they do, aside from being beautiful and fun). Bob Thomas wrote a biography that’s not too far from the autobiography, but the real coup de grace in the process was discovering Darden Asbury Pyron’s exhaustive and remarkable biography, Liberace: An American Boy. Not only is it a comprehensive study of Liberace’s life, it’s a piece of scholarship to be applauded, and simply one of the finest pieces of biography I’ve ever read. Pyron contextualizes his subject as a uniquely American phenomenon operating in direct response to the cultural and social conditions of the culture throughout his life. And that approach certainly resonated with me, given that my historian training taught me to analyze the world through exactly that lens. I also purchased a number of DVD collections of Liberace’s performances throughout his career. The only books about Liberace that existed in 2010 that I didn’t obtain were his cookbook (since I couldn’t find a copy), and Scott Thorson’s Behind the Candelabra (which I couldn’t find for anything less than $150 given it’s out-of-print nature, a price too dear at the time relative to what I thought it would unearth for me).

Milwaukee Repertory Theater and the Liberace Foundation for the Performing and Creative Arts also established a partnership around the premiere production, and the Foundation’s representatives provided me with a few of their own resources. The play exists in partnership with the Foundation today, and I’m delighted not only in the resurgence of interest in Liberace, but the accompanying upswing in Foundation activity, as well. Hopefully all of his wonderful artifacts will be back on display again soon in some manner so that they can continue to delight audiences.

Milwaukee Repertory Theater and the Liberace Foundation for the Performing and Creative Arts also established a partnership around the premiere production, and the Foundation’s representatives provided me with a few of their own resources. The play exists in partnership with the Foundation today, and I’m delighted not only in the resurgence of interest in Liberace, but the accompanying upswing in Foundation activity, as well. Hopefully all of his wonderful artifacts will be back on display again soon in some manner so that they can continue to delight audiences.

While I was waiting for all of that material to arrive (much of which came from small used book stores, given that the cultural awareness of and interest in Liberace in 2010 was significantly different from what it is today and almost all of it was out of print), I jumped on YouTube. And the first videos that I saw there were of a very young Liberace wearing a very tasteful tuxedo performing fairly straight-up classical songs and standards, sometimes in the context of little set-piece vignettes, on what seemed to be a very restrained, dignified, and technically ahead-of-its-time, black-and-white television program. I suppose—if I even thought about it at all, which I can’t say that I really did—that I’d always carried an assumption that he’d been an outsized performer for his entire career. But here he was, in a tuxedo and backed up by a trio fronted by his brother, George, working through mostly-traditional renditions of well-known piano compositions, with the music and his relationship to it at the center of the program. While one could argue for the era that that Liberace was also outsized in his own way, regardless, the juxtaposition between the 1950s TV Liberace and the sequins-and-feathers Liberace that I recalled from the 1980s was immediate and jarring.

It quickly became clear that that evolution in performance style and packaging was a conscious choice. And the more that I explored that choice (as well as its inspirations and impacts), the narrative frame of the play—as an exploration of the duality of human identity in the context of our public versus private selves—essentially created itself. That remained the question that propelled me through the research phase, as well as the “why” at the core of the play.

Eger: What were the things that surprised you the most on this journey into the life and the mind of an extraordinary artist and troubled human being?

Hazelton: I found Liberace’s biography not only continually surprising, but also very moving and of towering centrality to so much of 20th Century pop culture. The project quickly evolved from an assignment to a story that I passionately believed deserved—and needed—to be told, and one which held real value for audience members of any background.

Hazelton: I found Liberace’s biography not only continually surprising, but also very moving and of towering centrality to so much of 20th Century pop culture. The project quickly evolved from an assignment to a story that I passionately believed deserved—and needed—to be told, and one which held real value for audience members of any background.

I learned what a truly gifted performer he was. Not only as a musician—you can say what you want about his interpretations of the music since that’s a subjective taste-based assessment, but you cannot disparage Liberace’s technique and physical skill as a player—but as an accessible human being who worked in service of pleasing his audience in a genuine effort to share something meaningful with them in order to allow them to walk out in a better mood than the one in which they walked in. I find that very ennobling, and a performance perspective worthy of profound respect. I always figured that the glitz served to cover up a deficiency as musician or in stagecraft—but he didn’t have any.

Certainly, he faced challenging choices in trying to balance and mesh his personal and private lives—including some real no-win situations that did him and those closest to him irreversible damage. There’s a fascinating contradiction of savvy perception and childlike naiveté at the core of his personality that seemed to have led him into troubling situations where he was blindsided by a response that, in retrospect, should have seemed obvious for someone as skilled at taking the temperature of and connecting with large groups of people as he truly was, but I don’t see him as any more or less plagued by demons than any of the rest of us—his were simply magnified in proportion to his career and the scale of the character that he played. But it’s that naiveté and ultimate emotional innocence at his center that I think was warped by the personal attacks upon him, and which ultimately prevented him from having many normative personal relationships throughout his life. If there’s any tragedy in his life, I think it’s that—the inability to develop a balanced, stable, and full inner emotional life in light of him having to move through so much of his life as something “other” than his fully true self. And that, I think, is the lesson for us all in his story—the damage done when we can’t take at face value the totality and complexity of ourselves and those around us.

I do find him deeply sympathetic as a human being, and I think it’s unfair to characterize him as a victimizer if one does also not equally look at the ways in which he himself was victimized, and the degree to which he internalized what he seems to have deeply felt would be a genuinely destructive rejection should his sexuality become common knowledge. I found that every choice he made was as a result of learned behavior—a cause-and-effect relationship, that once one understands his core motivation (which I take to be a genuine desire to make as many people as happy as he possibly could—with the added bonus that it made him almost preposterously wealthy along the way!), I think very clearly casts his entire life as a set of choices and decisions made with that objective in mind relative to avoiding as many of the obstacles that stood in his way. Was he always successful? Of course not. Was he always his best self? Far from it. Did he do things that he probably dearly wished he hadn’t? Assuredly so. But given the inherent generosity of that objective (despite the benefits that he reaped in achieving it, he genuinely never seemed to have the elevation or betterment of the self as the primary end to his work), it’s difficult for me to either judge him harshly or look upon him as some kind of monster, despite his having done some things in his personal life that could easily be categorized as monstrous. But, at the end of the day, which of us hasn’t? As Hamlet says of his father: He was a man, take him for all in all.

Eger: It must have been tempting to write an entertaining piece. What gave you the strength to become brutally honest with Liberace’s darker side?

Hazelton: I don’t think that I ever made a conscious choice to favor one over the other—nor do I think the two are mutually exclusive! My own favorite experiences in the theater are those that reveal something human and universal—where I learn something about myself and the world around me while I’m experiencing other human beings’ journeys. And that catharsis—for me personally, at least—is always delivered in the form of a human revelation that, in my own subjective opinion at least, seems to be fundamentally honest. It can be a primarily emotional journey that unlocks the intellectual, or an intellectual exercise the potency of which triggers a core emotional response. I like to think and feel in equal measure when I’m in a theater, and I think (hope?), that most people would agree with that. But it’s all in service of the revelation of human truth, and that honesty lives in the relationship between the light and the dark, the highs and the lows, and the triumphs and the failures.

Hazelton: I don’t think that I ever made a conscious choice to favor one over the other—nor do I think the two are mutually exclusive! My own favorite experiences in the theater are those that reveal something human and universal—where I learn something about myself and the world around me while I’m experiencing other human beings’ journeys. And that catharsis—for me personally, at least—is always delivered in the form of a human revelation that, in my own subjective opinion at least, seems to be fundamentally honest. It can be a primarily emotional journey that unlocks the intellectual, or an intellectual exercise the potency of which triggers a core emotional response. I like to think and feel in equal measure when I’m in a theater, and I think (hope?), that most people would agree with that. But it’s all in service of the revelation of human truth, and that honesty lives in the relationship between the light and the dark, the highs and the lows, and the triumphs and the failures.

And that philosophy dovetails nicely with Liberace’s own journey. So, for me, the exercise in creating the play was to determine my own specific, human viewpoint on Liberace’s life, figure out how that was relatable to human beings on a larger and more general level, and write that story in whatever way would make that truth resound most clearly. And, in this case, that meant a great deal of warmth and heart and what I hope people find to be some terrific laughs, as well as an honest exploration of his struggles. If they cry at the end, I don’t think they’re crying for him—I hope that they’re tears of recognition and relationship. Perhaps what I’m most proud of is that, during that 2010 production, the nightly cheering ovation was consistently led by obviously-straight men in their 50s and 60s. My assumption is that that was either out of apology for perhaps taking actions that resulted the most deeply in people outside of norms having to hide their differences, or from them being born into a generation with probably the most proscriptive gender roles in American history and therefore having to hide a great deal of their own selves to fit that limited definition of masculinity. I recall the father of a close friend saying to me through his own tears after one performance, “I wish I could knit.” We talked a bit about it, and as a child in the early 1950s, he loved to knit with his mother and grandmother. But his own father intimidated that desire out of him, and he gave it up. But fifty-some years later, he was still carrying regret that that wasn’t a thing he was allowed to do for reasons that likely impacted him fairly deeply as a young child. And, for that man, the damage done by his father’s refusal to let him knit was every bit as equal as the damage done through Liberace having to hide his own sexuality. People will decide the moral equivalence of those things for themselves, but, for me, that fifty-something straight white Protestant male achieved a profound level of empathy with Liberace, and, therefore, with any other person who might self-identify as gay. I don’t think as theater-makers that we have the power to directly change the world anymore. The audience is too small and popular tastes have shifted too much to other mediums. But we can change hearts and minds, one at a time, and if we can develop enough of a critical mass of those individuals, then meaningful change is possible. For me, that’s the point of the exercise.

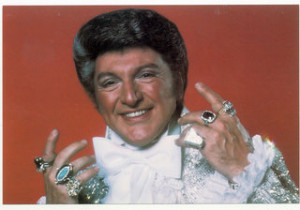

Jack Forbes Wilson as Liberace

That turned into a bit of a digression. Anyway, I also don’t know that we’re necessarily being brutally honest—though, of course, that depends on one’s definition of the truth of actual events. The Liberace that I’ve worked with since the inception of the piece, the almost criminally talented Jack Forbes Wilson, described the take of the play very well in an interview that we did together during the recent 2014 Milwaukee Rep remount. Every interviewer for that production asked us about the Steven Soderberg movie in comparison to the play, and Jack offered that they were attempting to achieve two different ends: if Soderberg’s movie was Behind the Candelabra (which, we should remember, is an adaptation of Scott’s book, not anything directly from Liberace’s own perspective), then our play could be considered to be “in front of the candelabra.” The focus is much more on the private events and personal choices that informed what his audiences saw and experienced than on any sort of exploration of a specific relationship between he and Scott (or he and anyone else, really). But, unlike the movie, the entire play takes place directly in front of an audience, with whom Liberace is having an in-the-moment conversation—and that relationship would also color the content of that conversation. So it’s not intended as a private confessional, but as a very intentional means by which Liberace can achieve something from that audience. And, as a reflection of that, thematically It’s about the relationship between him and his work and his fans and how the personal informed and influenced that—and, depending on one’s own perspective, whether that influence was for the positive or negative. So I don’t think that I consciously went for “dark,” nor would I if I had it to do over again—I went for honest and human, and disappointment is part and parcel of that experience.

Interestingly, when Jack and I started talking about the project (I had the luxury of knowing that I was writing it for him and working with him to shape it), we both wound up completely independently of one another with the same desired final image for the play—wouldn’t it be cool if we allowed Liberace the opportunity to strip away all of the glitz and just play a beautiful song, simply? We took the fact that we both landed on it to be a sign that that was at least an interesting idea, and that closing image informed my take on the biography and research, certainly.

But Jack’s really the strong one. He’s the one who has to get up there and do it every night for two hours with no net and only a piano and an audience as his scene partners. That ain’t easy.

Eger: LIBERACE is a twofer: a riveting play, and a concert, all rolled into one, not to mention the costumes, which, in addition to the music, represent the fourth dimension of the play. Could you describe the musical evolution of this piece, with you and Jack Forbes Wilson (what a name!) working out the musical numbers that would best represent Liberace’s music and your play? Again, here it seems that your research into Liberace’s world, and Jack’s knowledge of music and capacity to play certain pieces created a wonderful artistic cooperation between the playwright and the actor. Tell me more about that process.

Hazelton: I treated it as much structurally like a musical as I could, insofar as the music advances the narrative and reflects the intellectual and emotional themes in the play—while also making sure that there were enough of Liberace’s “go-to” songs in the show that fans would find familiar. So winnowing down that considerable catalog was a fairly easy task with those guidelines in mind—the story informed the songs. Add to that that we had only about five months from my getting the assignment and Jack being hired to play the role until opening night, and we also had to default in many cases to songs that Jack already had in his repertoire (which, thankfully, is nearly as vast as Liberace’s own). Jack did a marvelous job of “Liberace-ing up” his own arrangements (as well as creating some original show-stoppers), and continually made sure that we were making the right choices (I always argued; Jack was always right). All told, we wound up with almost three-dozen pieces of music intertwined within a nearly non-stop 105-minute monologue. It’s a brutal piece of work for a performer, but Jack never fails to carry it off with grace and charm.

But it’s also a sensational gift as a writer and director to be able to say to a performer, “Hey, I think here we’re going to do a monologue that covers 15 years of Liberace’s rise to superstardom in about four minutes, and you should play The Saber Dance while you say it,” and to then have the performer say, “Okay”—and do it! There are not a lot of people in the world who could do that, and I’m beyond lucky that we had one of the best already living and working in Milwaukee in Jack.

As for the costumes, Milwaukee Rep’s costume shop is nationally known in the industry for its level of quality and attention to detail. Our Costume Designer, Alex Tecoma, has been a member of that shop staff for almost two decades now, and has really come into his own as a designer of serious merit in the last ten years or so. He’s a wonderful friend and a great artist, and having him design the costumes was a no-brainer. And the costume shop and prop shop (also a nationally-known element of Milwaukee Rep under the leadership of Jim Guy), collaborated on all of the clothes that we see in the show that Liberace doesn’t wear. Again, it’s a real gift to be able, as a director, to suggest that level of detail and opulence on a relatively small budget and to have it come off so spectacularly. It’s a credit to the professionalism and craftsmanship of Milwaukee Rep’s artisans, and I’m proud to be able to share that work outside of the city as the show travels.

And I love the set that Scenic Designer Scott Davis has some up with, and the execution of it by our scene shop and in particular Milwaukee Rep’s paint shop, under the direction of Jim Medved, another of our nationally-lauded production artisans.

And three different lighting designers—Lee Fiskness, Aimee Hanyzewski, and now Scott Parker, continue to create the opulence and emotional landscape of Liberace’s world to great aplomb.

Eger: What were the most difficult parts of writing this play?

Hazelton: Figuring out the idea at its core. Once I could say to myself “It’s about love, dummy,” things dropped nicely into place. But it took a couple of months of writing myself down dead-end alleys to get there.

Eger: You integrated Philadelphia references, for example: when “Liberace” referred to the most outrageous outfit as a piece from the Mummer’s Parade, a statement that brought down the house. Tell me more about your research into Philadelphia references that you integrated into this version.

Hazelton: I honestly can’t take credit for that. As originally conceived for a Milwaukee audience, there were no shortage of local geographical and cultural references that delighted the audience (which, I think would hold true for any audience—people enjoy seeing themselves reflected on stage, and if it’s done in such a way that doesn’t feel like pandering, can be a strong force in uniting a room as well as telling a story using collectively relatable terms and concepts). Liberace himself, who toured extensively and developed relationships with individuals and communities that he returned to over and over again, would also try to localize his performances as much as possible. I think this is another example of his generosity of spirit both onstage and off: approach people on their own terms. Make them feel familiar and at home and welcome, and do them the courtesy of learning something about them while you’re with them. We learned early on in the original 2010 production that if something worked for Liberace (whether it was a specific moment or joke or overall philosophy), it was going to work for us, too, given that Liberace had spent years refining his stagecraft. So we applied that lesson to the localizing references, as well.

When Walnut Street committed to presenting the show, one of the first things that I sent Siobhan Ruane, Walnut Street’s terrific Associate Production Manager, was a list of all of the Milwaukee references for which we were hoping to find Philadelphia substitutions. There were about a dozen, if memory serves, and Siobhan put together a little Philly “local color” team who made terrific suggestions about just the right substitutions, both in tone and fact. We wound up finding good solutions for about eight of them. The other four we just cut, as they weren’t totally germane to the core narrative anyway, but the Mummer joke didn’t surface until we were actually in the theater, and the resonance with that giant feathered costume on stage was just too good to pass up for the natives in the room who saw it unveiled.

Eger: Are you and Jack planning to take this piece on the road and adapting it to the various localities, the way you did with the “Eagles song”?

Hazelton: If it continues to travel, it will continue to be adapted to reflect the locality in which it’s being presented. There are actually suggested substitutions written into the script, and presenters or producers are encouraged in select, noted moments, to shift references to suit their communities.

As for its future, Jack wanted to use the Philadelphia run to see if the piece worked outside of Milwaukee before committing to any further productions. So we’ll know in a few weeks what that verdict is, and we’ll assess from there. But the property is available for licensing (through Steele Spring Stage Rights), and will have been independently produced by about a dozen other companies by the end of next year since its licensing release in 2013.

Eger: Is there anything else you would like to share?

Hazelton: Here’s another question that Walnut asked that I thought was interesting.

Q. What’s different about your version of Liberace than other portrayals of the artist?

A. At the time we created it, other than some Saturday Night Live sketches and the odd impersonator here and there, I don’t know that there were many other portrayals out there. Certainly nothing in a “legit” stage play…at least that I knew of. Since then, there’s been the Soderbergh HBO movie, and how the news that Liberace will be back on tour again—as a hologram! And Lady Gaga continues to name drop him in lyrics. So he’s definitely vaulting back into the public consciousness over the past decade, and deservedly so. But my goal in telling his story (relative to those short-form comedy exercises certainly), was to really reach for something honest, real, balanced, and fundamentally human that hopefully reaches the level of universally-applicable metaphor—to reach back to that initial fascination with my own discovery of him as something other than a drag clown in millions of sequins and a couple hundred pounds of seashells or feathers, and find the real guy.

But, aside from that, after 3000 words, I’m feeling a touch dry at the moment. So, no, not right now. Feel free to shoot back anything that you’d like further clarified or expanded, and I’ll do my best. Thanks again for your interest!